Written by Junhyung Han

Abstract

In this paper, I contemplate ways to make people voluntarily care about the environment and endeavor to ameliorate environmental problems. I aim at justifying the conclusion that if people engage with the environment, they care about and voluntarily becomes responsible for preserving its integrity. To do so, I argue for two following premises: (P1) if people engage with their (everyday) environments, then they care about and voluntarily becomes responsible for preserving their integrity and (P2) the environment (i.e. the biosphere) is their (everyday) environment. To validate P1, I deviate from traditional environmental aesthetics and argue for the necessity of what I call the ‘aesthetics of our environments.’ Also, I come up with two antithetical concepts, ‘engagement’ with and ‘exploitation’ of (everyday) environments through a conceptual analysis using a paradigm example. Then I argue that people’s engagement with their everyday environments guarantees their care about that environments. To validate P2, I zero in on one major disanalogy between everyday environments and the environment and argue that the uniqueness of the environment does not preclude people from engaging with it in a way that they do with their everyday environments. Finally, I complete this paper by suggesting a possible way to facilitate people’s engagement with the environment.

§1. Introduction

I happened to read Walter Sinnott-Armstrong’s “It’s not my fault: Global Warming and Individual Moral Obligations” as a part of a philosophy seminar. There he begins with an intuitively reasonable claim, that we have a moral obligation not to drive a gas guzzler just for fun, and tries to support it with commonly accepted moral principles. After surveying a number of moral principles, he concludes that there seems to be no moral principle that reliably undergirds the intuitively obvious claim and thus we cannot claim to know that driving a gas guzzler for fun is morally wrong.1 Many years have passed since the paper was published and in the meantime, someone might have found a moral principle that justifies that particular moral intuition. But that paper was enough to make me question whether ethics can truly move people’s hearts, at least when it comes to environmental concerns.

Such doubt is hardly new. Karsten Harries purports that we need a “change of heart” that transcends the reach of “cold reason” to change the way we relate to the environment.2 He is convinced that there is no argument strong enough to force those whose interest does not concern the well-being of the posterity to forgo their credo, “after me the deluge.”3 Harries suggests recourse to environmental aesthetics and urges us to feel that we exist as parts of nature and thus acknowledge that nature is our home.4 On the other hand, Hans Jonas contends that inculcating people with a fear of mass destruction—what he calls “the heuristics of fear”—may bring about what wisdom and political reason could not.5 Although he does not think that the heuristics of fear is not “the last word in the search for goodness,” he considers it at least “an extremely useful first word.”6 Despite the difference in their suggestions, both Harries and Jonas seem to agree that moral reasoning alone falls short of motivating people to take action.

In this paper, however, I will not attempt to lay out a well-established metaethical theory of why ethics fundamentally falls short of changing our hearts, for what matters for my argument is the mere fact that people’s awareness of environmental issues does not reliably lead them to take enough action.7 Instead, I presume the inefficacy of ethics and suggest that we supplement our half-heartedness by engaging with the environment, which I consider an aesthetic solution.

My argument in this paper will be as follows:

P1: If we engage with an environment, then we care about (and voluntarily become responsible for) preserving its integrity.

P2: The environment is an environment.

——————————————————————————-

C: If we engage with the environment, we care about (and voluntarily become responsible for) preserving its integrity

Sections 2-4 focus on justifying P1 by providing relevant background information, defining key terms, and instantiating the concepts using a paradigm example while Section 5 focuses on justifying P2 by establishing a connection between what I call ‘an/one’s environment’ and ‘the environment’ to reach the conclusion. (The distinction between the two is introduced in the following paragraph.) A more specific overview of the paper is as follows: in Section 2, I briefly introduce everyday aesthetics and explain why we need to consider the ‘aesthetics of our environments’ a distinctive subcategory of everyday aesthetics. In Section 3, I develop concepts of ‘engagement’ and ‘exploitation,’ which are two different relationships we can have with our environment. In Section 4, I claim that we care about and voluntarily become responsible for preserving the integrity of environments with which we engage. And in Section 5, I argue that we can engage with the environment by means of setting up a proxy for it and suggest a possible way to promote our engagement with the environment.

Before I move on, I would like to clarify that what I call ‘an/one’s environment’ and ‘the environment’ are distinct. The former refers to a physical space wherein one spends a significant amount of time performing her average-everyday tasks while the latter refers to the biosphere, i.e., the totality of places on earth that are inhabited by organisms. I acknowledge that the concept of an/one’s environment invites numerous controversies—including those over how much time is enough to be considered significant, whether, say, a building next to my house should be considered my environment, etc. But insofar as we are not exorbitantly obsessed with such line-drawing problems and can intuitively tell whether a space is one’s environment or not, I presume that readers will not have any difficulty reading the rest of the paper.

§2. Everyday Aesthetics and the Aesthetics of Our Environments

There seems to be a general agreement that visual pleasure is by no means the only concern of aesthetics. Two counterexamples are aesthetic cognitivism and the aesthetics of engagement. Aesthetic cognitivists contend that our knowledge about what is appreciated significantly affects our perception of its beauty or ugliness. For instance, when people found out that Jason Allen used an artificial intelligence program to generate his artwork for an art competition in Colorado, many of them were infuriated and immediately devalued the work.8 Another interesting case is scientific cognitivism, which underscores the roles of our (natural and social) scientific knowledge of human environments in our aesthetic appreciation of them.9

On the other hand, aestheticists of engagement go beyond art and nature and highlight any interactive process between the experiencing agent and the object of experience.10 They consider being immersed in and intermingled with the object of experience indispensable for aesthetic appreciation.11 Among them, everyday aestheticists zero in on such interactive experiences we have in our everyday lives, although which experiences should be counted as ‘everyday’ is contested.12 For instance, Melchionne defines ‘everyday aesthetic object/practice’ as quotidian (as opposed to episodic) activities and objects that transcend individual and cultural

differences—such as cooking, dressing, commuting, etc.13 In contrast, Puolakka argues that such a definition of everyday is too narrow and Procrustean.14 He would suggest that we have a notion of everyday wide enough to encompass average-everyday activities of those with unique occupations and lifestyles by focusing more on whether an activity of our interest is quotidian or episodic for those who are performing it.

The purview of traditional everyday aestheticists is primarily sensory: they think everyday aesthetics should zero in on immediate everyday sensory stimulation (e.g. the smell of oven-fresh croissants from a bakery next to one’s workspace, the sight of colorful autumn foliage on one’s way to walk her dog, etc.) or sensory stimulation that results from everyday bodily activities (e.g. chopping wood in the backyard, doing dishes in the kitchen, etc.). However, some recent everyday aestheticists countenance the continuity model, according to which our everyday aesthetic perception should be based on a prolonged (as opposed to momentary) relationship between us and the object we perceive.15 Instead of immediate, uncritical aesthetic judgments, the continuity model urges perceivers to make prudent, all-things-considered aesthetic judgments after interacting actively and reflectively with objects of perception.16

The continuity model of everyday aesthetics seems promising yet quite broad for accounting for the aesthetics of our environments, at which this paper aims. Consider two following cases. (1) I spend about twelve hours a day (i.e. 4,000 hours a year) in my room sleeping, studying, watching Youtube, etc. (2) During my trip to Paris, I happened to have a good 3-hour conversation with a total stranger I met in a cafe. In both cases, I might have come up with decent aesthetic judgments of the objects of experience—the room in (1) and the stranger in (2)—according to the continuity model. But then the continuity model would be assigning the episodic 3-hour conversation [(2)] and the most quotidian experience [(1)] in the same category, and doing so makes me question the usefulness of the model when it comes to demonstrating the uniqueness of the aesthetics of our environments.

Then in what sense is it unique? Recall from Section 1 that in order for a space to be our environment, we need to spend a significant amount of time doing average-everyday tasks. It is not the duration of time per se but rather what happens to our aesthetic perception of our environment during that time that makes the aesthetics of our environments unique. Sensory stimulation is often ephemeral and volatile. My brain retains neither the exact tanginess of vindaloo I had three weeks ago nor the exact whiff of hot humid air I inhaled when I first came to the U.S. for college several years ago. Also, we get habituated to a particular sensory stimulus and reflexively filter it out upon our prolonged exposure to it.17 For instance, when I first moved into my room last year, I had trouble sleeping at night because of the loud noise of a ventilator located nearby. But after a few months, I found myself being completely unbothered by the noise while my friend who visited my room was amazed by the noise. Due to the volatility of sensory stimulation and our disposition of being sensorily habituated, our repeated exposure to objects of experience makes us put more and more weight on rather non-sensory aspects of our experience of them.

Consider this example: imagine a person who makes money by selling snow cones in an amusement park. She loved working there for the first few days—she liked the sound of shaving ice, the smell of delicious waffles from a neighboring vendor, and the jubilant background music from a speaker. However, as time went by, other aspects of her job became more salient. She does not like that she is poorly paid, that she has to deal with rude customers once in a while, etc. Three months have passed since she started working, and the only thing that keeps her working there is the fact that she needs to pay her rent in a few days, and her aesthetic perception of her work environment is now subpar. This example seems like an accurate exemplification of what happens to our aesthetic perception after our repeated exposure to objects of experience. As the person was more exposed to her work environment, the convivial, festive sensory stimulation that she enjoyed for the first few days became no longer decisive in determining her perception. Rather, the cognitive aspect (that she is poorly paid) and the emotional aspect (that she is disrespected by rude customers) contributed significantly to her perception of her job and accordingly, her perception of that environment.

Because of such uniqueness of the aesthetics of our environments that stems from the long duration of experience, it seems reasonable for me to create a subcategory for the aesthetics of our environments under the continuity model of everyday aesthetics.18 That way we can characteristically distinguish the aesthetic experience of our environment [like (1)] from the aesthetic experience of what is not our environment [like (2)] though they both are instances of the continuity model. Having established the new category, I would like to introduce new terms that are unique to the category.

- Relate-oneself (v.) To initiate and/or maintain one’s experience of a space.

- Relationship (n.) A connection between an agent and a space that forms and develops as a result of her relating-herself to the space.

Two points to keep in mind. First, the concept of relating-oneself is similar to the concept of ‘engagement’ in the aesthetics of engagement. The reason I did not use the word ‘engagement’ here is that I later use it to describe a more specific type of relating-oneself in the following section. Second, I used ‘a space’ instead of ‘an environment’ in the definitions to suggest that one can relate-oneself (and thus can have a relationship) to a place wherein she has not spent a significant amount of time for it to be considered her environment. Nonetheless, my focus still remains on an/one’s environment, not a mere space.

In this section, I have given a brief overview of everyday aesthetics, explained the necessity of creating a subcategory exclusive to the aesthetics of our environments, and defined the terms ‘relate-oneself’ and ‘relationship.’ In the following section, I will introduce two different relationships one can have with her environment using an example that instantiates the relationships.

§3. Engagement and Exploitation

I would like to begin this section by offering examples that will help me explain two opposite concepts, engagement with and exploitation of an environment.

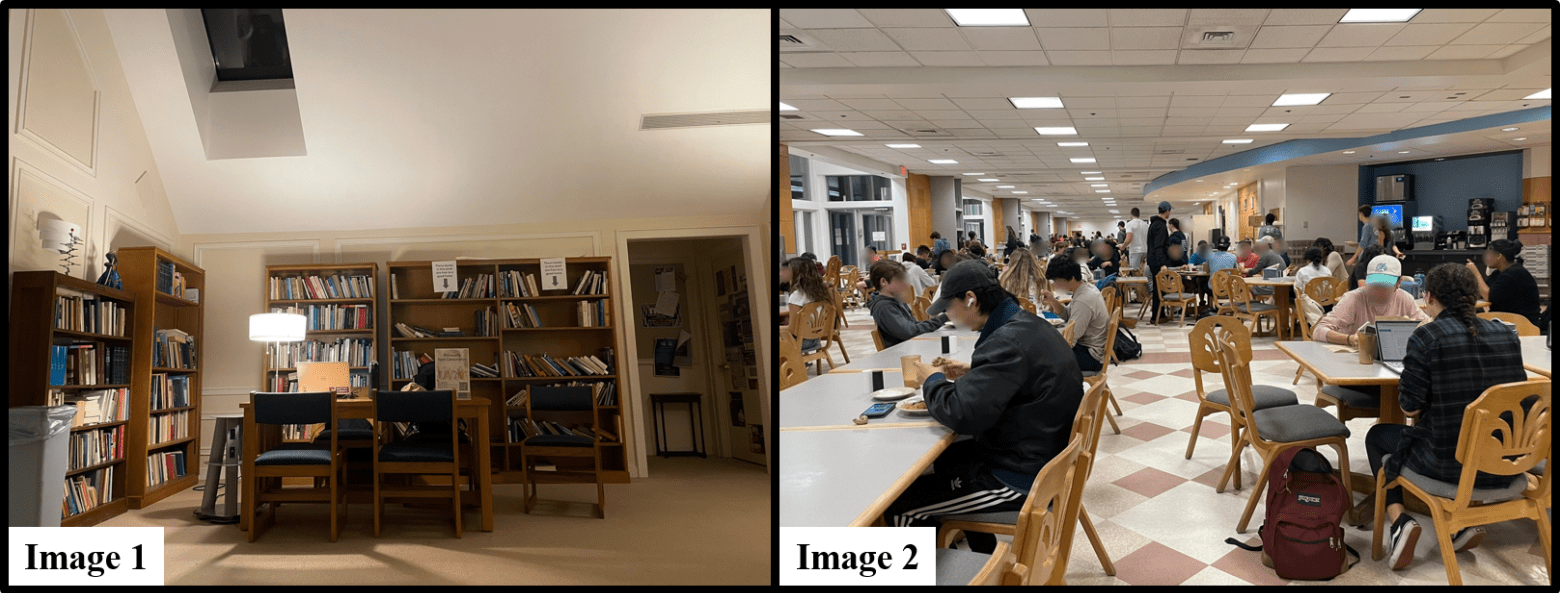

My favorite place on campus is the eastern end of the third floor of the Humanities Center, a historic building founded in 1923. (Refer to the image below.) It is a cozy space with bookshelves full of old philosophy books, a humble wooden desk with a table lamp, and couches and cushions with fabric covers. I started going to that place mainly because my favorite professors’ offices are there, but now I have my tutoring hours, read philosophy, and write papers there. I enjoy being there especially at night since all lighting is indirect and warm-colored, which keeps the place dim, ambient, and calm when I am there alone.

On the other hand, one of my least favorite places on campus is the main refectory. (Refer to the image below.) During lunch and dinner hours, that place becomes so crowded that I have to take extra care not to collide with other people when I carry plates. The combination of the crowd, low ceiling, pale fluorescent light, and odd arrangement of tables makes me uneasy. I cannot help being frustrated whenever I see people thoughtlessly discarding used napkins and disposable cups in the bin with a sign that says “food scraps ONLY.” People yell, bang tables, and burn bread in toasters, making it impossible to dine without distracting myself with conversations with friends or watching videos using noise-canceling headphones.

It may be helpful for readers to know that I am a student living on a small college campus and that I do not have a car. That means such circumstances force me to relate-myself to places on the campus regardless of my disliking.

What can we make of the contrast between the Humanities Center and the refectory? Based on our previous discussion, we know that I am relating-myself to both spaces. We also know that both spaces are my environments, for I spend a significant amount of time in both spaces doing my quotidian tasks. Let us then focus on the difference between the two. The most salient difference is that I spontaneously spend time in the Humanities Center while I reluctantly spend time in the refectory. Even when I am not visiting professors’ offices or having tutoring hours, I overcome a moderate desire to just work in my room, pack my bag and get dressed, and walk a few minutes to spend some meaningful time in the Humanities Center. On the other hand, I hardly go to the refectory except when I need some food despite that I have unlimited meal swipes and that there is a short indoor route that connects my dormitory and the refectory.

One may object and claim that I go to the refectory spontaneously, for I am going there to get some food I need without anyone’s coercion. To that objection, I would like to make two points. First, setting whether I am coerced or not as a criterion for determining the degree of spontaneity seems inappropriate for the purpose of this paper, for we are discussing aesthetics, not free will and moral responsibility. For instance, unwillingness to wear clothes that you think are ugly is enough to determine their beauty/ugliness even without being forced to put them on. Second, I would hesitate to call such purely instrumental visits spontaneous. This point may be further undergirded by the following: the refectory serves quality ice cream (and I love ice cream), but I do not spend time there reading philosophy or doing homework while I generally like doing it at cafes. The fact that I still prefer the Humanities Center by far even though the refectory has some relative advantages—such as having unlimited access to ice cream, being closer to my dormitory, etc.—seems to imply that such instrumental goods are neither sufficient nor necessary for spontaneous relating-oneself.

Another objection I anticipate is that this spontaneous vs. reluctant relating-oneself distinction is ultimately reducible to the well-known distinction between intrinsic vs. instrumental motives for forming relationships. Whether my motives for relating-myself to the refectory are intrinsic or instrumental seems quite easy to tell. The two only reasons I go there are that I need food/drink and that the space is conducive to socializing. Both motives seem to be aiming at some instrumental values the refectory has, so I would not hesitate to declare that my relationship with the refectory was instrumentally motivated. But whether my motives for relating-myself to the Humanities Center are intrinsic or instrumental seems harder to tell. For instance, is a desire to be there an intrinsic motive, or is it an instrumental motive? If we reframe this desire and say that it is a desire to be in a beautiful space, it starts to seem more instrumental, for I am utilizing that space in order to satisfy that desire. But if the desire is my mere disposition and I am inclined to act according to my dispositions, then my relationship with the Humanities Center is just a result of it-is-what-it-is, in which case we have a better reason to consider the motive of the relationship intrinsic. But aside from this difficulty, some of my motives for relating-myself to the Humanities Center are evidently instrumental: I go there because it boosts my work efficiency; I go there to visit my professors’ office hours, etc. Through these examples, I can assert with some confidence that the spontaneous vs. reluctant relating-oneself cannot be reduced to the intrinsic vs. instrumental motives for forming relationships.

Now I would like to introduce two terms that characterize my relationships with the Humanities Center and with the refectory and keep on contrasting the two places using the terms.

- Engage (v.) To relate-oneself to an environment spontaneously, i.e., one’s intrinsic motives of relating-herself outweigh her instrumental motives of relating-herself.

- Exploit (v.) To relate-oneself to an environment reluctantly, i.e., one’s instrumental motives of relating-herself outweigh her intrinsic motives of relating-herself.19

According to these definitions, I engage with the Humanities Center while I exploit the refectory. I consider engagement a concept opposite to exploitation, but it is crucial to understand in what aspect they are opposite. We should not mistakenly think that engagement and exploitation correspond to positive and negative emotions respectively. Negative emotions are not necessary for exploitation to happen. We can easily think of an exploiter who exploits an environment apathetically, not out of animosity or vengeance. So in terms of the emotions involved, engagement and exploitation are not directly opposite. Instead, they are directly opposite in terms of the spontaneity of relating-oneself, as shown in the contrast between relating-myself to the Humanities Center and relating-myself to the refectory.

Both engagement and exploitation are matters of degree. We can engage more with an environment and less with another; we can exploit an environment more and another less. But I think engagement and exploitation are mutually exclusive concepts. In other words, we cannot engage with an environment that we exploit and cannot exploit an environment with which we engage. This may seem too strong of a claim, but the underlying reason is quite simple. We previously discussed that we engage with an environment when our intrinsic motives of relating-ourselves to it outweigh our instrumental motives while we exploit an environment when our instrumental motives outweigh our intrinsic motives. Since it is contradictory for the instrumental motives to both outweigh and not outweigh the intrinsic motives at the same time, it seems reasonable to conclude that the two concepts are mutually exclusive.20

In addition, the two concepts are jointly exhaustive. In other words, our relationship with an environment needs to be either engagement or exploitation but cannot be neither. The reason is simple. We do not seem to continue relating-ourselves to a place if it is neither intrinsically nor instrumentally valuable. One may object by providing a counterexample: if one moves to a new house, she indeed seems to relate-herself to the new house even if she does not yet know well about its intrinsic/instrumental values. That example, however, does not undermine my claim because I used the word ‘continue.’ We tentatively relate-ourselves to a place until we figure out whether it is valuable or not simply because there is no way to do so without relating-ourselves. Just as we try out a new TV for a month for free before we reliably assess its value to confirm our purchase, we try out a space by tentatively relating-ourselves to it and decide whether we will continue the relationship (either in an engagement mode or an exploitation mode) or sever it.

In this section, I have characterized the two modes of relating-oneself to an environment—engagement and exploitation. Refer to the table below for a summary.

But what do all these conceptions of engagement and exploitation have to do with a change of our hearts? I will reply to that question in the following section by explaining that engagement with an environment leads us to care about its integrity.

§4. Engagement: A Key to Preservation

Let us go back to the example of the Humanities Center vs. the refectory. Thinking about the two environments, I found out that I treat the former and the latter differently. When I work or study at the Humanities Center, I wipe the table if it is sticky or has food crumbs on it. I turn the table lamp off and arrange the chairs when I leave. And I frown when I see anyone stretching their feet on the couch or the coffee table with their shoes on. On the contrary, when I dine at the refectory, I do not always wipe the table if I am not the one who made a mess. If there are more chairs than a table is supposed to have (which usually is a fault of the group that used the table earlier), I do not eagerly look for a table nearby that lacks a chair so that I can bring it back. In short, I cherish the Humanities Center and act spontaneously in ways that preserve its integrity while at the refectory, I often do not volunteer to do more than the bare minimum, remaining indifferent about preserving the integrity of that place.

Such differential attitudes do not pertain only to those two environments. People have qualms littering at, for instance, a national park while on their way to it, they have fewer qualms throwing trash out of their car window. We can list such examples ad nauseam. To my shame, when I was younger and immature, I threw away cherry pits and eggshells in bushes along the sidewalk a few times, exonerating myself by telling myself that they are tiny and biodegradable. Was that act morally commendable? Absolutely not. But was that subpar moral sense the major cause of that action? To that question, I would hesitate to say yes, for back then, I never discarded anything that is tiny and biodegradable elsewhere even though I did not undergo any moral epiphany and no one else was looking at me. Then what else was the problem?

For both my differential attitudes toward the Humanities Center and the refectory and my past moral blunder, I think what dictated me to act in such ways that are (dis)respectful of my environments is my aesthetic perception of them. Remember that there was no agential difference in both cases: it was I who wiped the table at the Humanities Center and who did not at the refectory. I demonstrated such different attitudes even though my moral sense remained constant. So moral sensibility being the major cause sounds unconvincing. Let us consider another possibility. It is a well-known fact that we use public goods more carelessly than private goods. Can this be why? Not quite, for both the Humanities Center and the refectory are public spaces. Some may object by pointing out that relatively fewer people use the former while almost all students use the latter, which may imply that the latter is more public than the former. But considering how I keep my dorm room—an undeniably private space—messier than the Humanities Center, the public-private theory does not seem convincing. Ruling out the two possibilities that seemed salient to me, it seems more likely that the difference in aesthetic perception was the major cause of such differential attitudes.

Based on the examination of the examples, I think it is reasonable to argue that we care about preserving the integrity of an environment with which we engage. Simply put, if we engage with our environment, we care about it. It is worth contemplating the word ‘care’ for a moment. What kinds of things do we care about? The most immediate answer would be: we care about things we like. Then is care equivalent to penchant? Not quite—unlike the word ‘penchant,’ ‘care’ has two starkly different meanings: (1) provision of what is necessary (including one’s attention) for maintaining the integrity of the object of care and (2) worries and anxiety.21 But even when we mean the former, we seem to unwittingly imply the latter as well. If we do (1) for X, it implies that we would do (2) in some imaginary, possible, or even counterfactual situations wherein X goes wrong. Considering that our engagement with our environments is spontaneous, when we care about those environments, we are spontaneously yet often unwittingly (though the combination of these two words is oxymoronic) risking being worried and anxious by conceiving or witnessing situations wherein those environments lose their integrity. And risking such psychological burden and rendering ourselves vulnerable to distress for the sake of those environments seems to imply that (1) caring can be far more personal than a mere penchant and (2) we almost undertake responsibility for our environments without being compelled to do so.

This distinction between care and penchant is clear when we compare our environment with a place we like but is not our environment. For instance, during my trip to Paris last summer, Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte was my favorite place. From each chamber of the château to the fireworks at night, everything was just enough beautiful but not too flamboyant. I have a penchant for that château, but it is not my environment because I have been there only once. I want that beautiful château to remain intact, but I would not be distressed if a visitor spills coffee on the carpeted floor of that château. The Humanities Center is extremely modest compared to the château, but it is my environment and I would be distressed and concerned if anyone spills coffee on the carpeted floor of that space even though custodians take good care of it. And if that is the case, I would be voluntarily demonstrating some kind of responsibility for (maintaining the integrity of) the Humanities Center.

So far I have taken a closer look at the relationship between care and environments with which we engage and shown that we are willing to take responsibility for maintaining the integrity of those environments. Then what about our environments that we exploit and thus do not care about its integrity? It is worth pointing out that we do not necessarily destroy an environment that we exploit—we are simply not interested in and feel responsible for actively preserving it. But even if no one maliciously destroys it, imagine what will happen if everyone takes advantage of it without putting any conscious effort to preserve it. Average-everyday wear and tear will accrue, and the exploited environment will be impoverished to the extent that there is no resource left to be exploited and will end up being deserted as exploiters look for yet another pristine environment to take advantage of. If this hypothetical case sounds oddly familiar, you are not alone. I think this is exactly (or a more optimistic description of) what has happened on our planet for the past few centuries. Here I will not elaborate further on the severity of environmental exploitation and the ensuing environmental crises we face nowadays, for I assume most people would know well enough about them.

In this section, I have purported that our relationship with our environment dictates whether we care about (and thus whether we voluntarily become responsible for) preserving its integrity. And it would naturally imply that in order to preserve the environment, we need to engage with it instead of exploiting it. Then are we all set to preserve it? Not so fast. In the following section, I shift my focus from an/one’s environment to the environment (i.e. the biosphere) to discuss our relating-ourselves to the environment. I will address one major disanalogy between an/one’s environment and the environment that ostensibly precludes our engagement with the environment, claim that engagement with the environment is nonetheless possible, and suggest a possible way to facilitate our engagement with the environment.

§5. Engagement with the Environment

Before I begin the section, let us pause for a moment to take stock. (Refer to the syllogism in Section 1.) Through Sections 2-4, I attempted to justify the premise ‘If we engage with an environment, then we care about (and voluntarily become responsible for) preserving its integrity.’ In this section, I will attempt to justify another premise ‘the environment is an environment’ in order to reach the conclusion ‘If we engage with the environment, then care about (and voluntarily become responsible for) preserving its integrity.

Thinking about the distinction between an/one’s environment and the environment (or the biosphere—I use both interchangeably) from Section 1, there seems to be a major disanalogy between an/one’s environment and the environment. In order for a space to be one’s environment, she needs to have spent a significant amount of her time performing her average-everyday tasks. Since most (if not all) people are always surrounded by the biosphere and do average-everyday tasks within it, the environment roughly seems like a type of an environment. But the major disanalogy is that the environment, unlike an environment (such as the Humanities Center, the refectory, etc.), is so massive that there seems to be no way one can engage with every single part of the environment. If engagement with the environment requires that she engages with every single part of the biosphere, can she ever engage with the environment?

My answer is ‘yes’—instead of engaging with every single part of the whole, one can set up a proxy that symbolizes the whole when it is inconceivably immense. This, in fact, is a common strategy people use to facilitate their engagement with something immense. The most straightforward examples are countries. A country consists of innumerably many elements: it includes every citizen, every inch of its territory, every code of law, every historical event, etc. What makes it even hard to perceive as a whole is that its constituents keep changing (e.g. its citizens come into being and pass away, its soldiers are recruited and discharged, etc.), making the totality of its constituents today differ from the totality of its constituents yesterday. But regardless of such issues and complications, people seem to have no problem conjuring up their countries just by looking at their national flags. When citizens of the U.S. see the Start-Spangled Banner, they think of the U.S. as a whole, not of its individual constituents one by one. In this example, the national flag is the proxy for the country as a whole. And we rely on proxies to effectively deal with the immensity of the wholes in many other cases. Another common yet remarkable case is that religious symbols like the cross serve as proxies for the religions and their God(s) as a whole. It implies that the strategy of setting up a proxy enables people to think of even metaphysical entities.

We can take a step further and query whether engagement with something immense, not mere ‘thinking of it,’ is possible. Considering that spontaneity is the key to engagement, I think engagement with something immense is possible. Let us take a look at the example of religions. In Christianity, there is no rule (that I know of) that commands Christians to spend a certain amount of time a day/week thinking about God. Devout Christians would spontaneously think about His glory, benevolence, etc. multiple times a day while some non-religious ones would do so only on Sunday morning or when their sudden need for His providence arises. In this case, I think it is safe to consider the former engaging with God more deeply than the latter. In the same principle, deep and sincere engagement with other immense things (such as countries) also seems possible.

I have so far argued that engagement with something immense (and even metaphysical) is made possible by means of a proxy. And if that is true, it seems to be a corollary that engagement with the environment as a whole would likewise be possible by setting up and engaging with a proxy that symbolizes it. Then the disanalogy between the environment and an environment does not seem to be a good reason to deny that the environment is a type of an environment.

One may ask: what should serve as a proxy for the environment? I have three criteria that a thing needs to satisfy in order to serve as a proxy for the environment. First, I do not think everyone needs to have the same proxy for the environment. For instance, some may use their backyards while others use the mountains they hike on weekends as their proxy for the environment. This flexibility is possible because people have different experiences—for instance, we cannot force those who have never lived in a house with a backyard to set a backyard as their proxy for the environment because they simply do not know well about what it is like to garden and spend time in a backyard. Therefore, when people’s experience varies, it seems reasonable to let people decide their own proxy that would facilitate their engagement with the environment.

Second, I think a proxy for the environment should be encountered and perceived frequently by those who use it as a proxy. Many Christians, for instance, carry a cross-shaped pendant or hang a sizable cross on the wall to encounter those proxies more frequently and be reminded of engaging with God more frequently. Perceptual cues are effective means of conjuring up related thoughts and memories (as the entire souvenir industry runs on that principle). In the same line of thought, it may not be a good idea for an average college student in the U.S. to set a forest in Brazil or glaciers at the North Pole as her proxy for the environment, for it is not what she would encounter and perceive often in her quotidian life.

Third, I think a proxy for the environment should be unambiguous. In other words, one’s proxy for the environment does not serve its purpose if it conjures up primarily something else than the environment. For instance, if a souvenir I bought from Rocky Mountain National Park reminds me primarily of, say, Yellowstone National Park, then the souvenir fails to serve as a proxy for my trip to Rocky Mountain. In the same vein, we may not want to have humans or artifacts, despite being parts of the biosphere, as a proxy for the environment, for they may remind us of technological and industrial advancement, which have been the main excuse for ravaging the environment, and thus seem to be at odds with our desideratum—namely engagement with the environment.

The three points I made suggest that we set non-human nature we often encounter and perceive in our average everyday as a proxy for the environment. So insofar as we have an adequate proxy with which to engage (i.e. spontaneously relate-ourself), we can engage with the environment as a whole. Then how do we engage with the proxy? As to the question of how, I honestly do not know the perfect solution. But I think I know where to start: we should start by stopping exploiting the environment. Theoretically, since engagement and exploitation are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive concepts (as elaborated in Section 3), a relationship that is not exploitation will necessarily have to be engagement.

This suggestion seems to be directly at odds with my previous account, for here it seems like I am forcing people to engage with the environment while I have previously argued that engagement can only be done spontaneously. In order to figure out whether I am really forcing engagement, we first need to see how our change in the relationship with the environment is possible. Let me explain it through an example. It seems true that we cannot start (dis)liking our friend/foe immediately after we desire to do so as if we turn a switch on and off. But when we are given a chance to interpret her personality in a different light, our judgment of her changes, and accordingly, our relationship with her is open to change. Likewise, if we are given a chance to change our notion of the environment, it seems certainly possible to stop exploiting and start engaging with the environment. This is a claim that aesthetic cognitivists can take over: (historical, scientific, etc.) knowledge of and beliefs about the environment can set the stage for our willingness to engage with it.

Then is such change in the relationship forced? My answer is ‘no’—I rather think it is unfair not to be provided any opportunity for such change. Let me borrow a concept from social epistemology to elaborate on why it is unfair. In her book Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing, Miranda Fricker talks about what she calls hermeneutical marginalization: the basic idea is that if one is given less or no opportunity to participate in a collective process of establishing a certain concept and ways to interpret it, she is hermeneutically marginalized.22 (While Fricker focuses on cases of hermeneutical marginalization that involves socially entrenched identity prejudice, I think the concept is applicable to a wider range of cases.) Fricker argues that those who are hermeneutically marginalized are susceptible to epistemic and collateral injustice. Considering how our knowledge of the environment affects our attitude towards and relationship with it, whether we have had our fair share of participation in establishing and maintaining the socially shared concept of the environment would dictate the legitimacy of the concept we have and the ensuing relationship we have had with the environment. I think we did not have our fair share. The notion of the environment as a mere repository of resources at our disposal has existed for a long time but has been maintained and consolidated by industrialists (especially of well-off countries) since the Industrial Revolution.23 And having inherited that notion, people nowadays likewise regard the environment as something reticently awaiting to be taken advantage of for human goods. For this reason, it is only fair for us to be given a chance to contribute to and reestablish the shared notion of the environment by actively engaging with the environment, and if it, accordingly, leads to a change in our relationship with the environment, the change is far from being forced.

Then how do we reestablish the notion of the environment? The best way I can think of is to give engagement with the environment a try, as my aforementioned example of a person who relates-herself to her new house (in Section 3). The younger the ones who give it a try (and thus are yet to fully develop their aesthetic perception and their notion of the environment), the more efficacious this strategy will be. As they develop the notion of the environment as a whole and set an appropriate proxy (according to the three criteria listed above) for the environment based on their experience of relating-themselves to the proxy, they will be able to engage with the environment. Take children to a backyard, farmland, and a national park. Let them see how dandelions grow over time in the backyard; let them witness how soil, water, and sunlight jointly nourish the crops and bemoan when they witness pesticides killing grasshoppers on the farm; let them be overwhelmed and speechless by the eons of geological history in the national park. What I ultimately suggest is a change in the way society educates people (especially children)—without hands-on engagement with the environment in the younger period of their lives, they will invariably inherit the old notion of the environment and perpetuate the exploitation of it. It will take at least a decade for such education to kick in. But it seems to be the only sure way to induce a fundamental change in the way people relate-themselves to the environment. In the meantime, the older generation will have to gain time by means of tighter regulations, preventing environmental problems from degenerating further.

§6. Conclusions

In this paper, I attempted to persuade readers to think that the recourse to environmental aesthetics, unlike the recourse to environmental ethics, is a promising way of moving people’s hearts and making them care about preserving the environment. By purporting that the aesthetics of our environments should be a distinct category under everyday aesthetics, I implied that the solution that this paper suggests is an aesthetic one and justified the need to come up with terms that are unique to that category (in Section 2). I defined the concept of engagement and exploitation using the antithesis between the Humanities Center and the refectory (in Section 3) and demonstrated that we care about and become voluntarily responsible for preserving the integrity of environments with which we engage while we are uninterested in preserving environments which we exploit (in Section 4). And by showing that we can engage with the environment as a whole by setting up a proxy that symbolizes it, I purport that the environment is a type of an environment and thus that, per the point I made in Section 4, we will be caring about preserving the environment once we engage with it (in Section 5). Finally, I suggested a change in the ways society educates people and having them try engaging with the environment (especially from the early stages of their lives) as the surest way I think is to fundamentally change their hearts and induce sustainable and voluntary efforts to ameliorate environmental crises.

The significance of this paper seems to be that it shows that the problem in traditional environmental aesthetics of determining whether the environment is inherently or only instrumentally valuable is not sophisticated enough to account for our aesthetic perception of and our relationship with the environment. By providing two novel frameworks—(1) aesthetics of our environments and (2) the idea that the environment is a type of an environment, not something that stands alone—this paper attempted to persuade readers to think that the ways they care about the environment are not at all a far cry from ways they care about their environments.

Endnotes

- Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, “It’s Not My Fault: Global Warming and Individual Moral Obligations,” in Perspectives on Climate Change, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong and Richard Howarth, eds. (Elsevier, 2005).

- Karsten Harries, “What Need is There for an Environmental Aesthetics?,” Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 22, no. 40-41 (2011): 13, https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v22i40-41.5186.

- Ibid., 15

- Ibid., 13

- Marion Dönhoff et al., “Not Compassion Alone: On Euthanasia and Ethics,” The Hastings Center Report 25, no. 7n (1995): 44–50, https://doi.org/10.2307/3528008.

- Hans Jonas, The Imperative of Responsibility (University of Chicago Press, 1984), 27.

- I will set aside an epistemological question of whether one really knows if the knowledge does not lead her to act in accordance with her knowledge, for that is beyond the scope of this paper.

- Kevin Roose, “An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy.” The New York Times, Sept. 2, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/technology/ai-artificial-intelligence-artists.html?smid=url-share.

- Allen Carlson, Nature and Landscape: An Introduction to Environmental Aesthetics (Columbia University Press, 2009).

- Allen Carlson, “Environmental Aesthetics,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta, ed., https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/environmental-aesthetics/.

- Arnold Berleant, “What is Aesthetic Engagement?” Contemporary Aesthetics 11 (2013), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.0011.005.

- Yuriko Saito, “Aesthetics of the Everyday,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta, ed., https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/aesthetics-of-everyday/.

- Kevin Melchionne, “The Definition of Everyday Aesthetics,” Contemporary Aesthetics 11 (2013), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.0011.026.

- Kalle Puolakka, “Does Valery Gergiev Have An Everyday?,” Paths from the Philosophy of Art to Everyday Aesthetics, Oiva Kuisma, Sanna Lehtinen, and Harri Mäcklin, eds. (The Finnish

Society for Aesthetics, 2019), https://doi.org/10.31885/9789529418787. - Giovanni Matteucci, “Everyday Aesthetics and Aestheticization: Reflectivity in Perception”, Studi Di Estetica 4, no. 23 (2022), http://journals.mimesisedizioni.it/index.php/studi-di-estetica/article/view/535.

- Saito, “Aesthetics of Everyday.”

- Tamar Podoly and Ayelet Ben-Sasson, “Sensory Habituation as a Shared Mechanism for Sensory Over-Responsivity and Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms,” Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience (2019), https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2020.00017.

- Note that the aesthetics of our environments cannot be reduced to environmental aesthetics, which predominantly

studies our appreciation of/relationship with the environment. - Note the difference between my use of the word ‘exploit’ and the use of the word in popular discourse. What people normally mean by ‘exploitation’ is a conniving and selfish act while what I mean by ‘exploitation’ does not necessarily denote something negative.

- One may wonder whether there is a way to precisely quantify all our motives and say, for instance, that “out of all my motives of relating-myself with my room, intrinsic motives are 72% while instrumental motives are 28%.” But such precision seems neither possible nor necessary for the purpose of this paper. Rather, being able to intuitively determine whether our relating-ourselves to an environment is spontaneous or reluctant seems enough for judging whether we engage with or exploit the environment.

- According to Dictionary by Merriam-Webster, the word ‘care’ came from Old Saxon kara (for ‘sorrow, worry’), Old High German chara, Old Norse kǫr (for ‘sickbed’). So it turns out that (2) is a more primordial use of the word ‘care’ than (1).

- Miranda Fricker, Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (Oxford University Press, 2017), 153.

- Theodore L. Steinberg, “An Ecological Perspective on the Origins of Industrialization,” Environmental Review 10,no. 4 (1986), 264, https://doi.org/10.2307/3984350; Donald Worster, “The Intrinsic Value of Nature.”

Bibliography

-

- Berleant, Arnold. “What is Aesthetic Engagement?” Contemporary Aesthetics 11 (2013). http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.0011.005.

- Carlson, Allen. “Environmental Aesthetics.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition). Edward N. Zalta, ed. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/environmental-aesthetics/.

- Carlson, Allen. Nature and Landscape: An Introduction to Environmental Aesthetics. Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Dönhoff, Marion, et al. “Not Compassion Alone: On Euthanasia and Ethics.” The Hastings Center Report 25, no. 7 (1995): 44–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3528008.

- Fricker, Miranda. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Harries, Karsten. “What Need is There for an Environmental Aesthetics?” Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 22, no. 40-41 (2011): 7-22. https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v22i40-41.5186.

- Jonas, Hans. The Imperative of Responsibility. University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Matteucci, Giovanni. “Everyday Aesthetics and Aestheticization: Reflectivity in Perception.” Studi Di Estetica 4, no. 23 (2022): 207–227. http://journals.mimesisedizioni.it/index.php/studi-di-estetica/article/view/535/.

- Melchionne, Kevin. “The Definition of Everyday Aesthetics.” Contemporary Aesthetics 11 (2013). http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.0011.026.

- Podoly, Tamar and Ayelet Ben-Sasson. “Sensory Habituation as a Shared Mechanism for Sensory Over-Responsivity and Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms.” Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2020.00017.

- Puolakka, Kalle. “Does Valery Gergiev Have An Everyday?” Paths from the Philosophy of Art to Everyday Aesthetics. Oiva Kuisma, Sanna Lehtinen, and Harri Mäcklin, eds. The Finnish Society for Aesthetics, 2019. 132–147. https://doi.org/10.31885/9789529418787.

- Roose, Kevin. “An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy.” The New York Times, Sept. 2, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/technology/ai-artificial-intelligence-artists.html?sm id=url-share/

- Saito, Yuriko. “Aesthetics of the Everyday.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 Edition). Edward N. Zalta, ed. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/aesthetics-of-everyday/.

- Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter. “It’s Not My Fault: Global Warming and Individual Moral Obligations.” In Perspectives on Climate Change. Walter Sinnott-Armstrong and Richard Howarth, eds. Elsevier, 2005. 221–253.

- Steinberg, Theodore. “An Ecological Perspective on the Origins of Industrialization.” Environmental Review 10, no. 4 (1986): 261-276. https://doi.org/10.2307/3984350.